What Is CBT?

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is a psychological treatment developed by Aaron Beck and Albert Ellis in the 1960s. CBT is one of the most popular and empirically supported therapy modalities. As the name suggests, cognitive-behavioral therapy targets both cognitions and behaviors.

Cognitions are processes involved in obtaining knowledge and understanding. Some examples are attention, perception, memory, and reasoning.

We use hundreds of cognitive processes each day as we make observations and interpretations, and draw conclusions about events in our lives. Some of these cognitions are automatic and subconscious. CBT helps us identify distorted automatic thoughts and modify them.

The second element of CBT is the modification of dysfunctional behaviors. Behaviors determine how much exposure one gets to different stimuli, and thus, can have important consequences. Consider an individual hurting from a nasty breakup. What happens if he decides to deal with the pain through behaviors as different as going for a walk, taking a hot shower, smoking, drinking, watching a sad movie, or reading a self-help book?

CBT teaches that behaviors influence thoughts and emotions, so we need to be mindful of how we behave.

As could be seen from the above description, CBT is based on the assumption that cognitions, behaviors, and emotions are interconnected. It further assumes that to change how we feel, we must change our behaviors and particularly our cognitions. So, although we are unable to change a stressful occurrence (e.g., getting rejected), we have the freedom and power to make ourselves feel better if we can learn to think and behave in more adaptive ways.

Common elements of CBT

Most forms of CBT include behavioral techniques (exposure therapy, relaxation training), and cognitive strategies (problem-solving, cognitive restructuring).

Let us briefly review these elements.

In exposure therapy, the client is encouraged to engage in necessary or valued activities (e.g., driving to work) that have been avoided due to intense fears and distorted cognitions. During therapy, the individual is taught how to challenge her erroneous thoughts and expectations (e.g., the assumption that driving is extremely dangerous). Subsequently, the individual is encouraged to confront her fears directly in real life (in this case, to actually drive).

Another CBT element is relaxation training.

Relaxation training comprises a variety of breathing practices, such as deep breathing (abdominal breathing) and equal breathing (equal inhales and exhales). It often includes progressive muscle relaxation as well. Progressive muscle relaxation involves tensing and relaxing different muscle groups (e.g., muscles of the face, neck, shoulders). This technique helps the individual become more aware of his muscle tension (and thus his level of stress and anxiety) throughout the day, and to relax his muscles whenever they become tense.

An essential component of most forms of CBT is problem-solving. Problem-solving training teaches clients the skills needed to solve real-life problems. In addition, it helps them learn to see problems not as insurmountable obstacles but as solvable challenges. As Nezu, Nezu, and Lombardo explain, in their book Cognitive-Behavioral Case Formulation and Treatment Design, people with good problem-solving skills are less likely to become anxious or depressed after experiencing a negative event.

Perhaps the most well-known element of CBT is cognitive restructuring. Cognitive restructuring involves identifying erroneous automatic thoughts and replacing them with more logical and evidence-based thoughts.

Some examples of thinking errors are black-and-white thinking, jumping to conclusions, making “should” statements, and catastrophizing.

Black-and-white thinking refers to the tendency to see things as only right or wrong, ignoring shades and complexities. Jumping to conclusions means reading minds or believing a negative conclusion without sufficient evidence. Making “should” statements means having concrete ideas and inflexible standards about acceptable behavior in oneself or others. Catastrophizing refers to the assumption that the worst-case scenario will likely come true.

Let me illustrate the effect of these thinking errors using an example concerning catastrophizing. Imagine you want to learn how to play baseball but, despite a month of practice, have had no success. If you were to reason that you will never learn to play baseball or any other sport, then you would be catastrophizing. Thinking in this way might cause distress and worsen mental health. In addition, it may negatively influence future behaviors. After all, why would you persist in practicing baseball (or ever try another sport) if you believe the odds are completely against you?

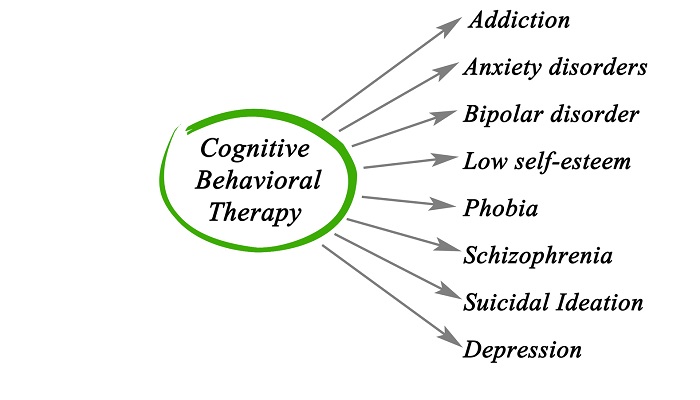

CBT for different mental health conditions

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is an effective treatment for many mental health conditions listed in the DSM-5, the diagnostic manual of the American Psychiatric Association. These conditions include, among others, anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, substance use disorders, and eating disorders.

Depending on the mental health issue under consideration, and the version of the treatment (e.g., traditional vs. contemporary CBT), the cognitive-behavioral intervention may comprise different elements.

Here are a few applications of CBT for common psychological disorders.

Anxiety disorders

CBT is the treatment of choice for anxiety disorders (e.g., social phobia, panic disorder). Take the case of generalized anxiety disorder, an anxiety disorder associated with excessive and uncontrollable worry and physical symptoms like fatigue, irritability, and muscle tension.

CBT for generalized anxiety disorder usually includes education, cognitive restructuring, and relaxation. Sometimes mindfulness meditation is also used.

Worry, being mainly a linguistic and cognitive process, is a way of avoiding the processing of emotional and visual experiences, particularly upsetting ones. Therefore, another aspect of CBT treatment of generalized anxiety is exposure to these experiences.

How does exposure to worry work? Suppose a student goes for therapy, complaining of debilitating worry before exams. The therapist might suggest the client imagine, in great detail, the worst possible scenario (e.g., failing the exam, and even the course). During this imaginal exposure exercise, the patient will be encouraged to open up to and accept the unpleasant feelings associated with this worst-case scenario. With practice, the exposure exercise helps reduce the unpleasant feelings and sensations that have been avoided; as a result, it may reduce the need for worry.

Depression

Major depressive disorder is characterized by depressed mood, lack of pleasure, weight and sleep changes, loss of energy, difficulties concentrating, psychomotor changes (e.g., slowing of movements), feelings of guilt, and thoughts of death. Several varieties of cognitive-behavioral therapies have been developed for the treatment of depression, with each emphasizing different aspects of CBT.

Many self-help books, such as the classic book Feeling Good by psychiatrist David Burns, focus on cognition in depression.

More behavioral versions of CBT for depression also exist. One is an approach called behavioral activation.

Behavioral activation is based on the premise that depression results from a lack of rewarding activities. The goal of treatment is to identify such rewarding activities and try to increase contact with them by including these activities in the individual’s daily schedule.

What kinds of activities? Those that improve people’s moods, are pleasurable and produce feelings of mastery. It is important to choose activities that are immediately rewarding.

Consider a depressed musician who values fitness and wants to get back in shape. Should this person commit to an hour-long workout session three times a week? Probably not. Why? Because although the fitness goal is valued and rewarding, the planned activity would likely be too challenging and not reinforcing enough. Less difficult and more immediately rewarding activities (e.g., dancing to music every day) would be preferable.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a psychological disorder associated with obsessions (recurrent urges and thoughts) and compulsions (repetitive behaviors). Compulsions (e.g., cleaning rituals) are performed in response to obsessions (e.g., fear of germs).

Exposure therapy is a mainstay of CBT treatment for OCD and involves both situational and imaginal exposure.

Suppose a client has obsessive fears related to germs and disease. He avoids many public places, particularly public restrooms. During therapy, the individual is instructed to use restrooms (situational exposure) and, furthermore, to imagine catching a disease (imaginal exposure).

These exercises increase the individual’s disease-related fears and thus the urge to engage in compulsions (e.g., taking multiple showers, going to the doctor for blood tests). But the other component of the treatment is response prevention, which means the individual needs to resist engaging in these compulsions.

Through practice, the client learns that the object of fear is not as dangerous as once imagined, high levels of anxiety can be managed without performing compulsions, and anxiety levels will go down through repeated exposure.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a psychological disorder associated with directly experiencing or witnessing trauma (events linked with death, injury, or significant violence). PTSD is characterized by intrusive memories of the trauma, avoidance of reminders of the event, increased arousal (e.g., difficulty sleeping), and negative changes in mood (e.g., persistent feelings of terror) and cognition (e.g., believing that nobody can be trusted).

Cognitive-behavioral treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder emphasizes exposure. A well-known exposure treatment for PTSD was developed by Edna Foa. The treatment, called prolonged exposure, is described below.

Suppose, soon after leaving a dance club, a young woman is raped by a stranger from the club. She then develops PTSD. The victim will probably avoid many internal and external cues (e.g., locations, people, sensations) related to the trauma of rape, such as sexual activities or going to clubs and other social settings.

In prolonged exposure therapy, the rape victim is encouraged to return to valued activities and objectively safe situations in a gradual manner. Over time, she will learn several things about the social settings and herself: These situations and activities (e.g., dance clubs) are not as dangerous as imagined, she has the ability to cope with difficult emotions, and her anxiety will decline through repeated exposure.

During the sessions, she is also encouraged to revisit the difficult memories of the rape. These sessions will be recorded, so the patient can listen to them at home. Repeated retelling and listening to the traumatic memories and experiences are intended to help organize memories of the event, make sense of the trauma, and reduce distress.

Substance use disorders

CBT is an effective treatment for substance abuse (the problematic use of drugs and alcohol). As McHugh, Hearon, and Otto explain, in their article in Psychiatric Clinics of North America, CBT for substance abuse may include motivational interventions, contingency management, and relapse prevention.

Motivational interventions address ambivalence toward behavior change. After all, it can be difficult to change long-standing drug-related habits. And a patient who is not sufficiently motivated might not be willing to put in the effort required.

At the heart of the treatment is contingency management. Because drugs are powerful reinforcers of behavior, the goal is to provide non-drug related rewards (e.g., privileges, vouchers for retail goods, a chance at winning prizes) for abstinence or reduced drug use. These rewards need to be highly valued. Of course, a lack of funds may limit the effectiveness of this approach.

Relapse prevention and related interventions are also crucial. They involve teaching coping and drug refusal skills, social skills needed to engage in rewarding activities that do not involve drugs, identification of cues for substance use, prevention, and avoidance of situations associated with use (e.g., being alone with a friend who is a drug user).

Eating disorders

CBT has been used for the treatment of a number of eating disorders, one of which is anorexia nervosa. Individuals with anorexia nervosa consume very little food, have abnormally low body weight, feel extremely afraid of becoming fat, and have distorted perceptions regarding their weight or the importance of weight to self-evaluation.

One version of CBT used for the treatment of anorexia is called CBT-E (E stands for enhanced). According to an article by Grave, El Ghoch, and colleagues, published in Current Psychiatry Reports, CBT-E is based on the following assumption:

The overvaluation of weight and shape and the importance of needing to control them are at the core of many eating disorders. In addition, CBT-E assumes low self-esteem, perfectionism, and interpersonal issues present additional obstacles to change in some individuals with anorexia.

The basic goal of CBT-E is to change distorted cognitive processes, like the mindset that mislabels some experiences as “feeling fat,” or assumes feeling that one’s clothes are tight is a sure sign of being fat. Such erroneous thoughts maintain disordered eating.

To challenge these cognitions, CBT-E uses behavioral strategies, education, and self-monitoring. It also addresses concerns regarding weight and shape, helps the client set behavioral goals for achieving and maintaining weight gain, and teaches skills for managing moods and setbacks.

Concluding thoughts on CBT

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is one of the most studied and empirically supported treatments for many psychological disorders. CBT assumes cognitions, emotions, and behaviors are linked. Because changing feelings directly is difficult, CBT offers a variety of techniques for changing feelings indirectly by modifying thoughts and behaviors.

Not only is CBT an effective treatment but it may also be used as a preventive measure. Distorted thinking and maladaptive behaviors can make even healthy people more vulnerable to psychological disorders. Everyone could benefit from studying CBT, and learning how to make accurate observations, think rationally, draw conclusions based on evidence, and behave more effectively in different situations.

If you are seeking treatment for a mental health concern or psychological disorder—particularly if you value a treatment that employs a direct and logical approach—then you might find CBT quite helpful.